ALOCASIA LONGILOBA

ORIGINAL DESCRIPTION:

Photo by The Gardener’s Center

SYNONYMS:

HOMOTYPIC SYNONYMS: N/A

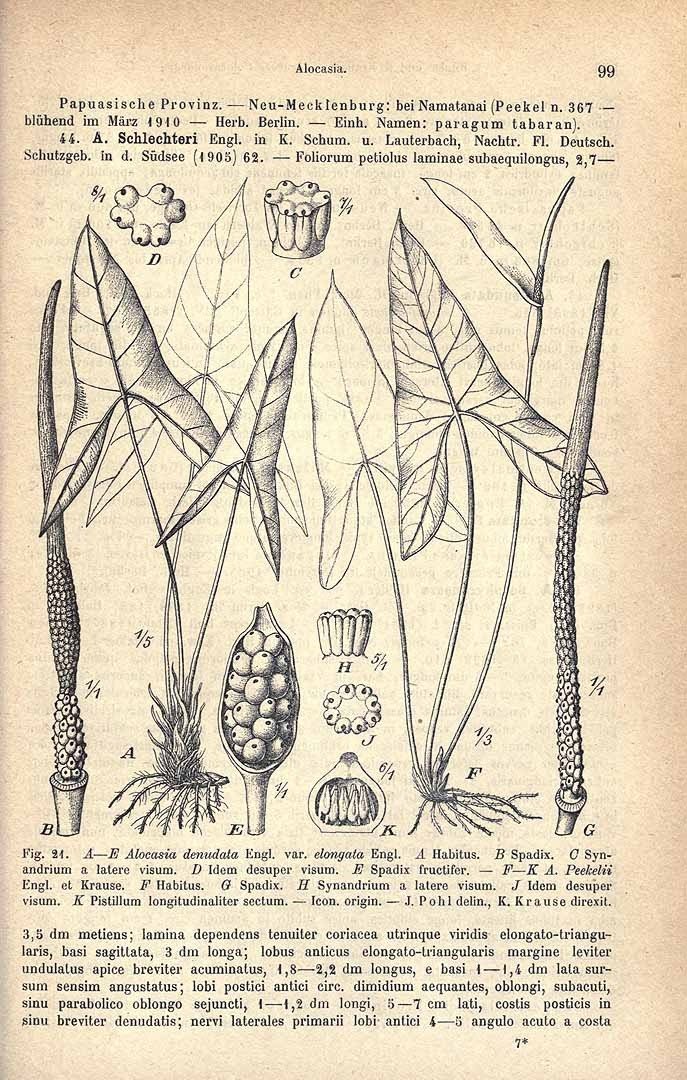

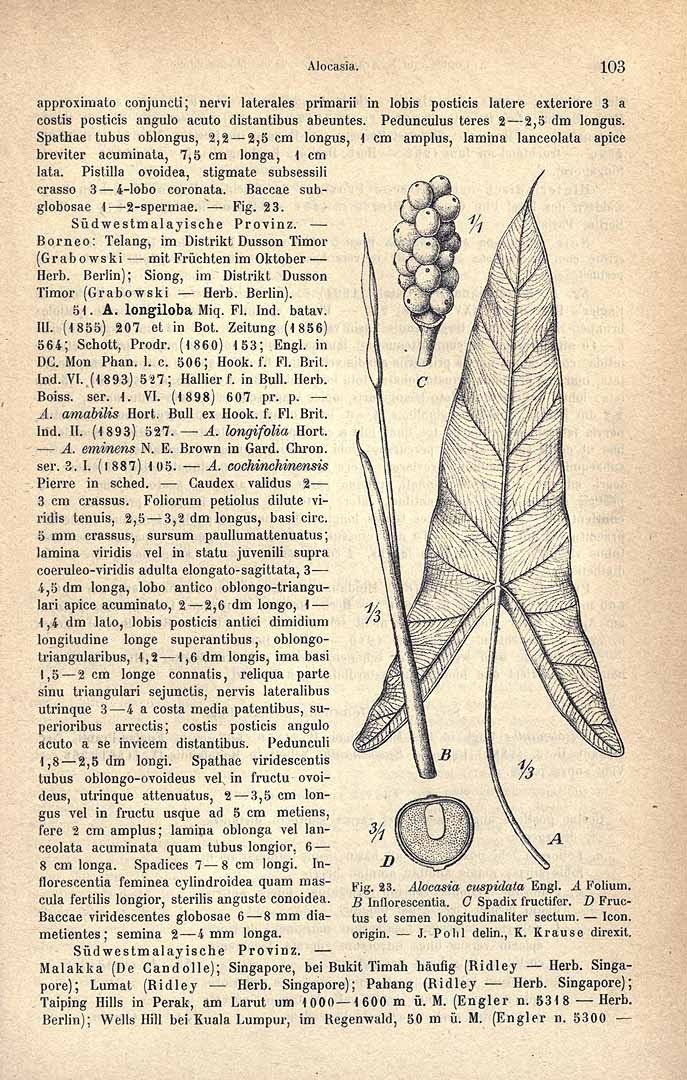

HETEROTYPIC SYNONYMS: Alocasia amabilis, Alocasia cochinchensis, Alocasia curtisii, Alocasia cuspidata, Alocasia denudata, Alocasia denudata var. elongata, Alocasia eminens, Alocasia gigantea, Alocasia grandis, Alocasia korthalsii, Alocasia leoniae, Alocasia longifolia, Alocasia lowii, Alocasia lowii var. grandis, Alocasia lowii var. picta, Alocasia lowii var. reticulata, Alocasia lowii var. veitchii Alocasia singaporensis, Alocasia spectabilis, Alocasia thibantiana, Alocasia veitchii, Alocasia veitchii var. supurba, Alocasia watsoniana, Caladium lowii, Caladium veitchii

ACCEPTED INFRASPECIFICS: N/A

DISTRIBUTION: Indochina to West and Central Malesia excluding the Philippines

CLIMATE: Tropical humid climate

Humidity is moderate throughout the year, ranging from 60% to 70%

Temperature is varies between the seasons - within the range of 48°F/9°C to 88°F/31°C during the day. Minimum temperatures never dip below 45°F/7°C

Rainy and humid season (October to May) and a dry season between June and October. The average annual rainfall is 1,200 mm

ECOLOGY: In rainforest and swamp-forest floor, regrowth, on boulders in forest and on exposed cliffs and ravines at low to medium elevation

SPECIES DESCRIPTION:

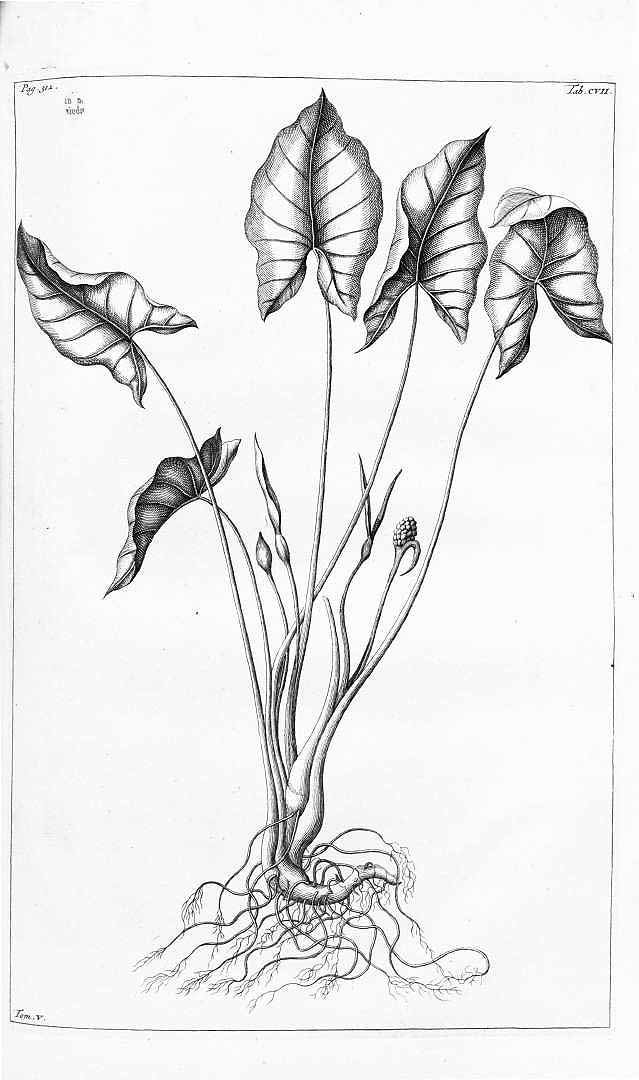

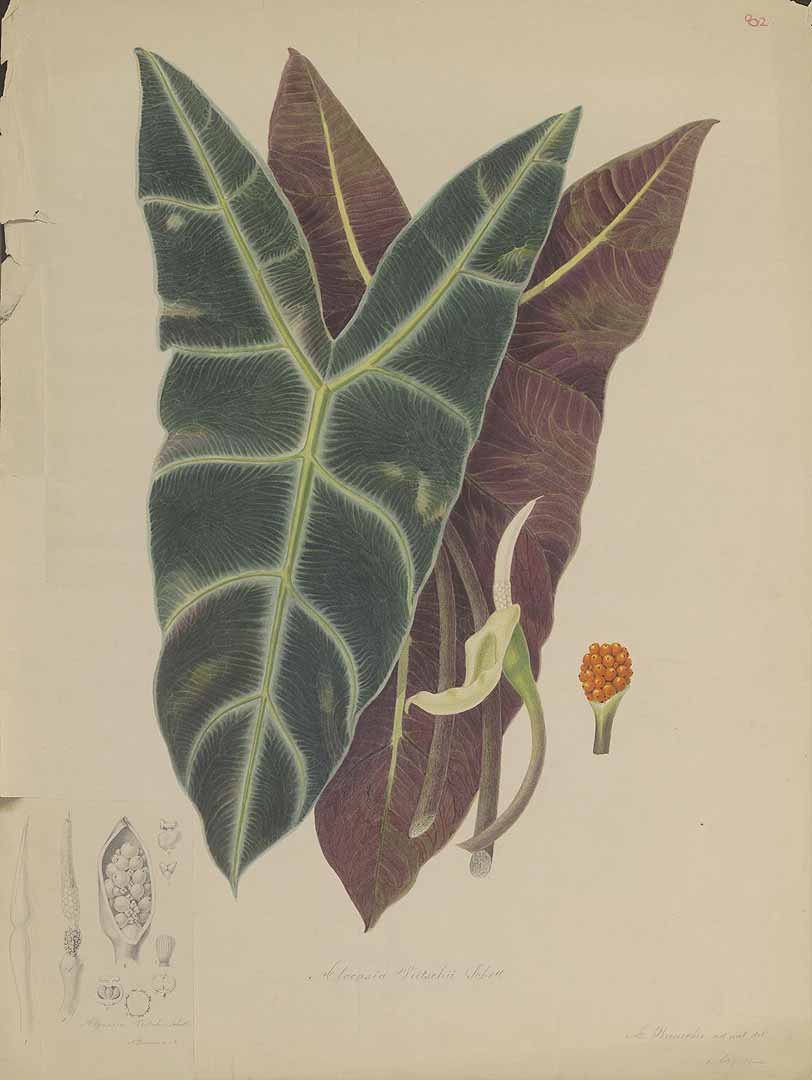

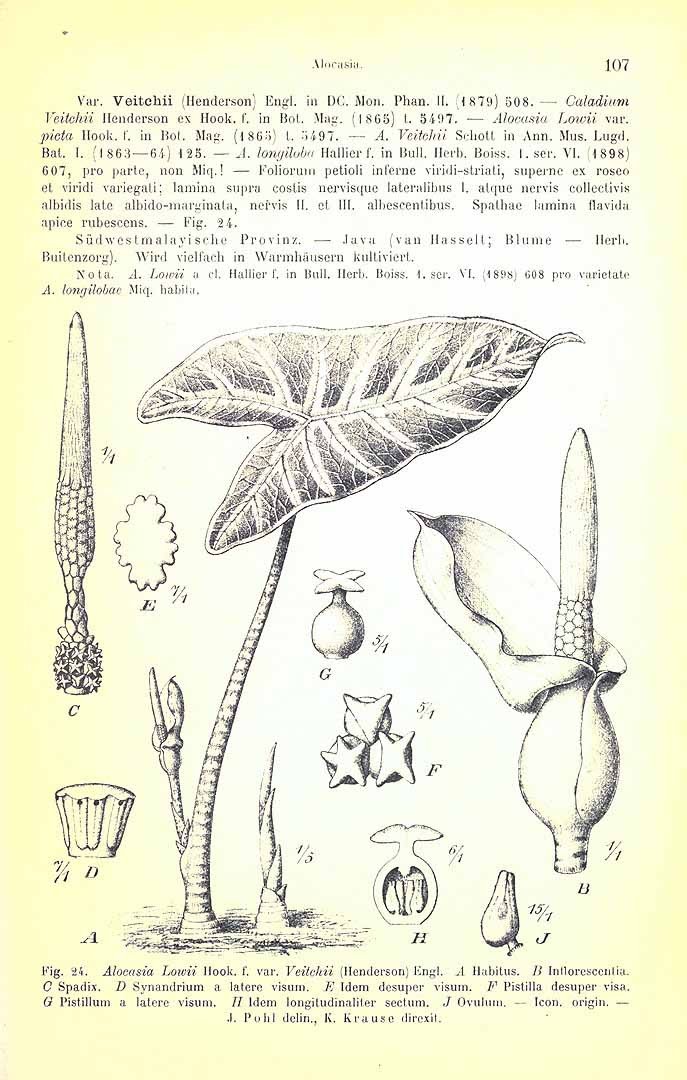

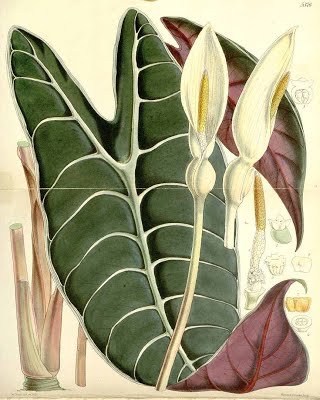

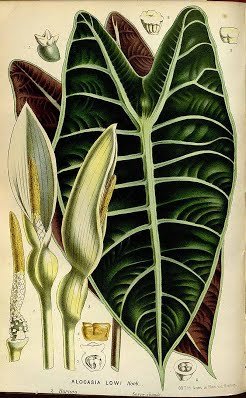

Small to robust herbs ca. 40-150 cm tall; terrestrial to lithophytic; rhizome generally elongate, erect to decumbent, often completely exposed, sometimes swollen and sub-cormous, ca. 8-60 cm long, 2-8cm diam., usually bearing remains of old leaf bases and cataphylls; growth markedly rhythmic with renewal growth delayed after flowering; vegetative modules often unifohar (to 3-leaved), subtended by conspicuous lanceolate paperymembranous often purpUsh-tessellate cataphylls degrading to papery fibres; petioles glabrous, purple-brown to pink to green, often strikingly obliquely mottled chocolate brown, ca. 30-120 cm long, sheathing in the lower ca. 1/4 or less; blades often pendent, shape and venation extremely variable, peltate (except 'denudata'), plain mid-green throughout to adaxially dark green and abaxially rich purple, often adaxially with the major venation white to pale grey-green and sometimes with the lamina bordering the main veins grey-green, hasto-sagittate and triangular in outline to ovatosagittate and shield-shaped, 27-65 (-85) cm long x 14-ca. 40 cm wide, with the widest point anterior to the petiole insertion to near the tips of the posterior lobes; anterior costa with 4-8 primary lateral veins on each side, the proximal ones diverging at ca. 60-100°, the angle decreasing in distal veins and the course more or less straight to the margin to markedly acropetally deflected; axillary glands conspicuous abaxially at the junctions of the main veins and costae; secondary venation obscure to conspicuous abaxially, mostly arising from the primary veins at a wide angle then sooner or later deflected towards the margin, forming variously well-defined interprimary collective veins or these absent, concolorous with the abaxial lamina or sometimes markedly paler; interprimary collective veins when present weakly undulating to strongly zig-zagging at broadly acute angles; posterior lobes ca. 3/4 to V2 the length of the anterior lobe, when peltate united for (5-)10-66% of their length; posterior costae straight to pedately incurved

INFLORESCENCE:

Inflorescences (solitary to) paired, with up to 4 pairs in succession without interspersed foliage leaves; peduncles ca. 8-18 cm long, usually resembling the petioles in colour and markings, erect at first, then often dechnate, elongating and then erect in advanced fruit, subtended by a series of progressively larger cataphylls resembling those of the vegetative phase; spathe ca. 7-17 cm long, abruptly constricted ca. 1.5-3.5 cm from the base; lower spathe green, ovoid to subcylindric; limb pale green, membranous, lanceolate, canoe-shaped and longitudinally in-curved, eventually reflexing after male anthesis; spadix somewhat shorter than to subequalling the spathe, ca. 6-13 cm long, stipitate, with the stipe conic, whitish, to 5 mm long; female zone 1-1.5 cm long; ovaries subglobose, ca. 1.5-2 mm diam., green; stigma subsessile or on a slender style to ca. 0.5 mm long, white, acutely and conspicuously 3-4-lobed, the lobes pointed, more or less spreading; sterile interstice 7-10 mm long, narrower than the fertile zones, corresponding with the spathe constriction; lower synandrodia often with incompletely connate staminodes, the rest elongate rhombohexagonal, flat-topped; male zone subcyhndric, somewhat tapered at the base, 1.2-2.5 cm long, 4.5-8 mm thick, ivory; synandria more or less hexagonal, ca. 2 mm diam., 4-6-merous; thecae opening by apical pores not overtopped by synconnective; appendix 3.5-9 cm long, about the same thickness as the male zone and demarcated from it by a faint constriction, subcylindric, distally gradually tapering to a point, faintly rugose to rugose in the lower part, very pale orange to bright yellow; fruiting peduncle to 25 cm long; fruiting spathe ovoid, ca. 4-7 cm long; fruits orange-red.

VARIEGATED FORMS: WHITE, MINT, YELLOW

ETYMOLOGY: The specific epithet, longiloba, refers to the long lobes that are characteristic of this species

NOTES:

1. In developing a classification that reflects what is at present known of this complex, I have avoided reducing its elements blithely to a single species without a clear quantification that it is not equivalent to a 'simple' species of low variation content. However, the complex cannot have forced onto it overstated and simplistic hierarchical discontinuities that would be implied in recognizing separate species and/or infraspecific taxa within it on the basis of currently available evidence (cf. Gentry, 1990).

Like many Alocasia species, the elements of this complex freely hybridize in cultivation, but within this group hybrid series involving three or four 'species' are recorded (see Burnett, 1984), confirming their close relationship. Many of the formally named parent forms are highly ornamental and striking, and the horticultural community may be irritated by their disappearing as named species. However, there is no reason why these names cannot be transposed into the nomenclature for cultivated plants as cultivars or cultivar groups. The background to the description of 'species' within this complex has been largely horticultural, through the introduction of the finest and most striking forms to European stove culture in the 19th Century. These forms represent what I have called the 'peak variants' in the complex, and I have used their types and associated nomenclature as a framework for the informal infraspecific classification proposed here. The entities proposed cannot at present be regarded as more than peaks in an overall continuum of variation and so not all specimens encountered can be categorically accomodated in this classification. Nevertheless, there are perceptible but incompletely resolved geographical patterns to the variation, and some ecological variation, which is somewhat but incompletely correlated with morphological variation and geographic pattern, discussed under the relevant 'peak variants'. The key provided to these variants must be regarded as a guide only to 'typical' forms, and no pretence is made that by using it all specimens encountered can be unequivocally identified.

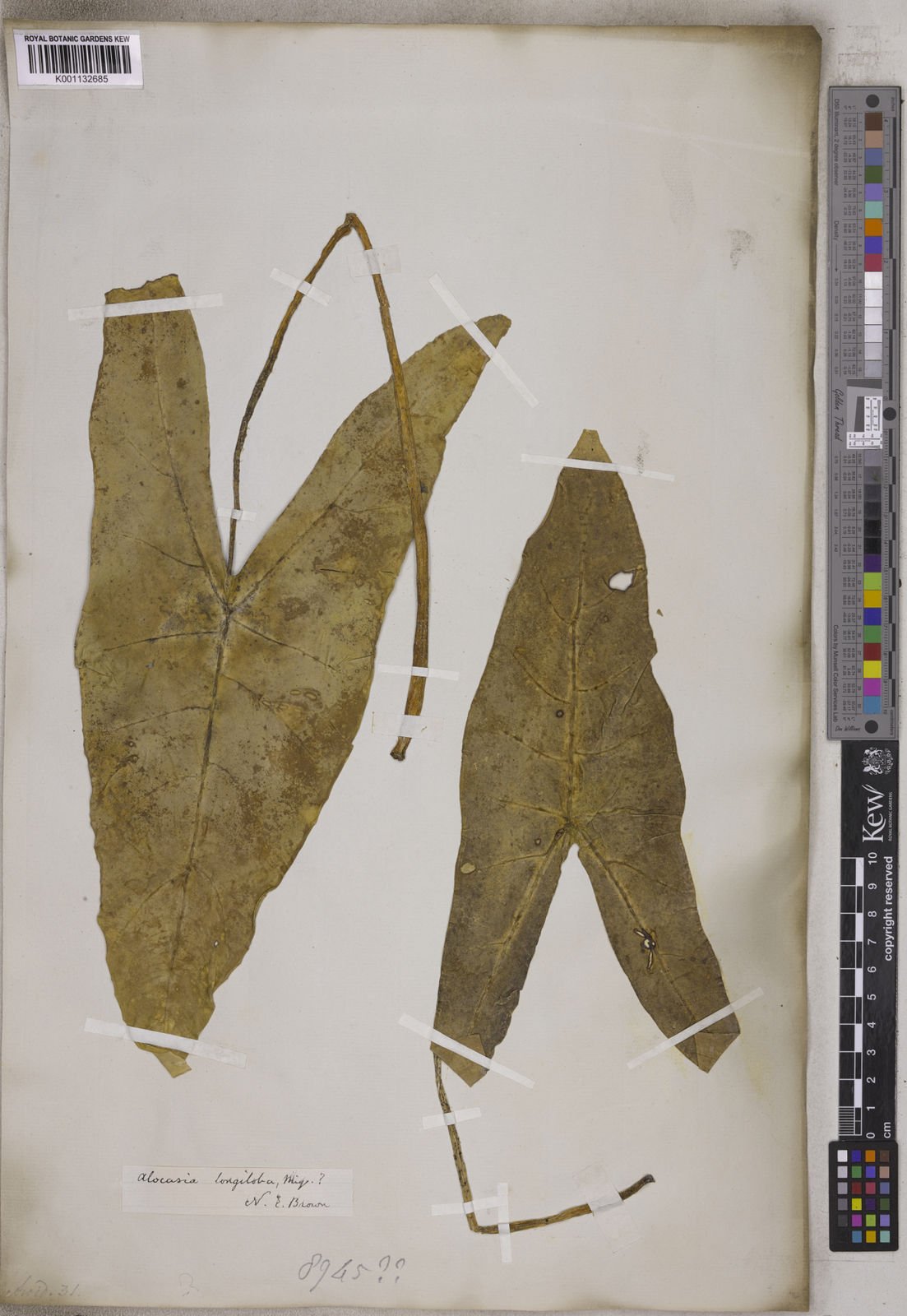

2. This complex can be considered an ochlospecies since, while there is a continuum of variation globally, at particular localities sharply differing forms may coexist and evidently behave locally as discrete sympatric 'topospecies'. A rigorous analysis of variance might reveal statistically significant narrow discontinuities, which could form the basis for species distinctions at the global level. However, at present, carrying out such an analysis is impeded by the inadequate and very uneven sampling over the range, exacerbated by the incompatibility of this genus with standard herbarium preservation methods. As a consequence of this incompatibility, collections consist of conveniently sized leaves or fragments which cannot be deemed comparable between individuals when the plants are known to show considerable plasticity of form depending on age and environmental factors.

The local coexistence of distinct forms presupposes the existence of local reproductive isolating mechanisms regardless of whether or not these might translate into the defintion of species within the complex globally.

The percentage of specimens preserved directly from the wild that bear inflorescences is extremely low and inadequate to form a basis for detecting isolation mechanisms based on flowering time. Moreover, there is an almost total dearth of ecophysiological data on finer aspects of phenology, which are known to be complex in this genus involving intricate patterns of flux in thermogenesis (Leick, 1915 - n.v., cited in Grayum, 1990) possibly associated with scent production and the differentiation of pollinator preferences.

3. Lindley described Caladium? veitchii from a cultivated plant obtained from Borneo. No original material has been located, and Lindley did not illustrate it. When Schott (1863) made the combination in Alocasia, he cited a collection by Kuhl and van Hasselt, from Java, in addition to noting the original provenance Borneo. Since Schott was the world authority on aroids at the time and had established an enormous collection of living plants, it is highly probable that he knew Caladium veitchii first hand. I therefore consider it enough to be guided by Schott's interpretation and designate the Kuhl & Hasselt specimen as the neotype.

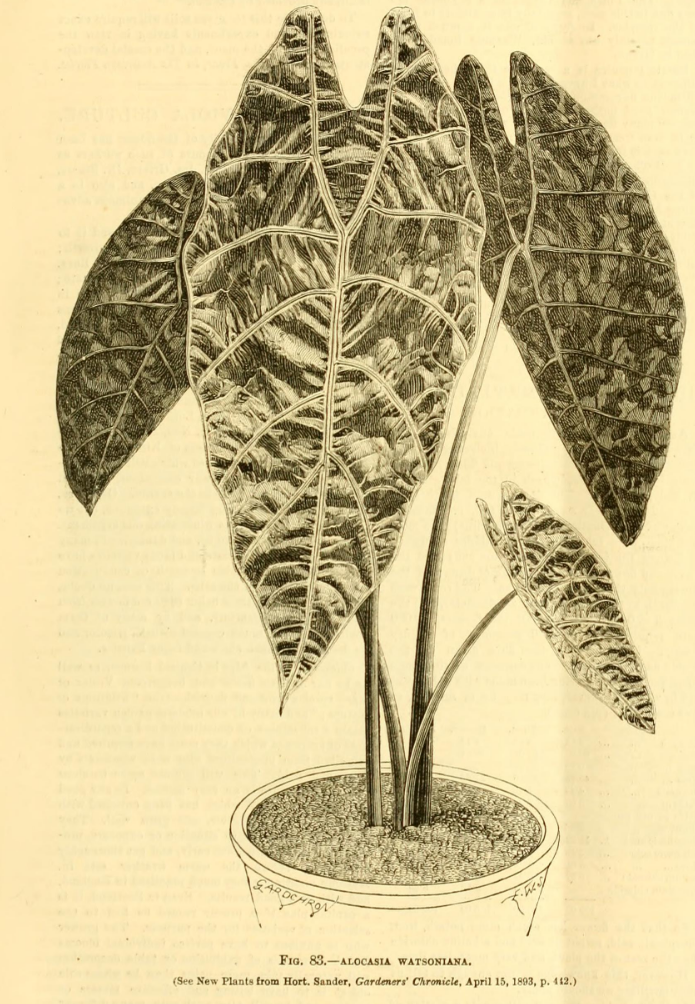

4. The above-cited illustration of Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’ is of a sterile plant, though it shows the distinctive bullate blade and in-curved posterior costae. It does not actually accompany the protologue, having appeared in an issue of Gardeners' Chronicle one month later. However, the caption includes direct reference to the protologue. Whether or not direct connection may be inferred between the illustration and the protologue, application of the name requires to be estabUshed more firmly. The above-selected epitype is preserved from a flowering cultivated plant of, evidently, the same clone introduced by Sander & Co, which Masters described.

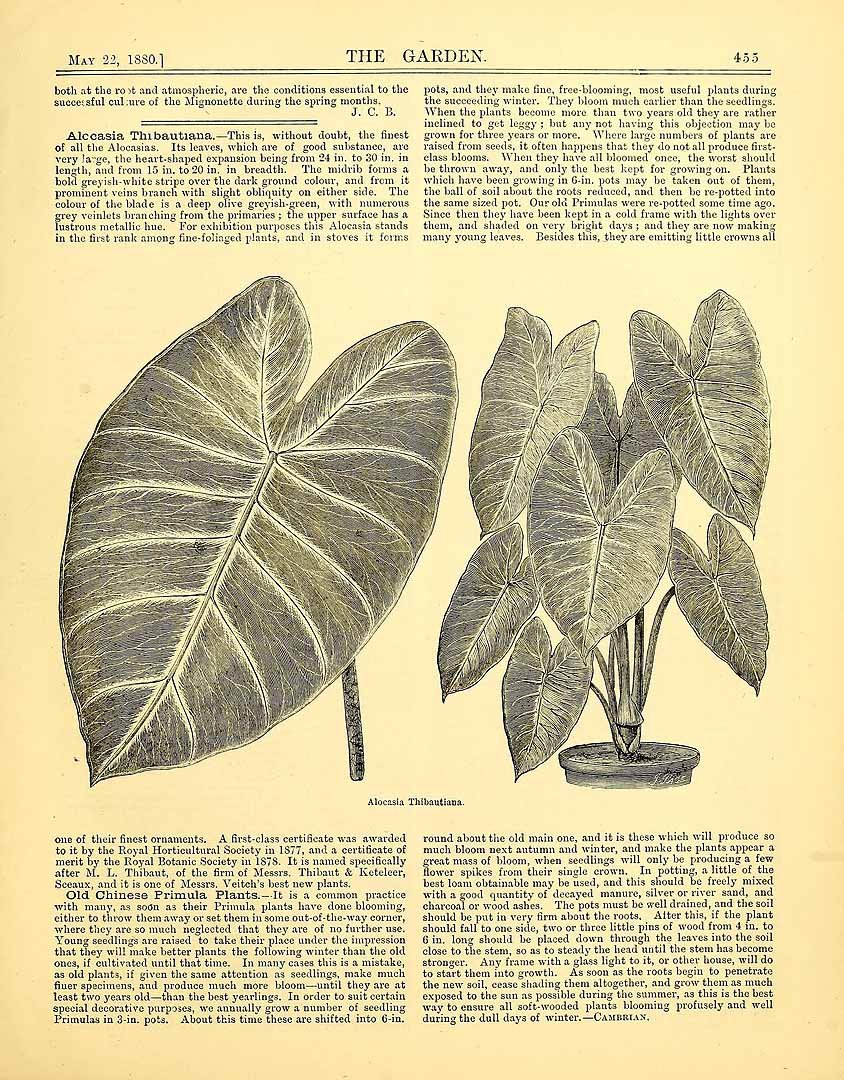

5. No material was preserved of Alocasia thibautiana when it was first described, nor was it illustrated. The designated neotype consists of two sheets annotated by N.E. Brown 'from the type plant'. Both consist of leaf only. A third sheet, dated 12 November 1881 consists of a dried inflorescence.

6. Linden's description of Alocasia singaporensis is extremely scant, reading, from the German, 'From Singapore. The large leaf is arrow-shaped, with large spreading basal lobes and of dark green colour'. Assuming the provenance Singapore alludes to origin from the wild, this description can only match Alocasia longiloba 'denudata'. Material preserved by Brown at Kew under the name Alocasia singaporensis is indeed of that entity.

7. Alocasia denudata var. elongata Engl, was differentiated from the typical variety by the narrower lobes of the leaf blade. The designated neotype well exemplifies this state. The illustration that accompanied the protologue is not good enough to serve as the type in the absence of the material it was apparently based on. There are no details of leaf venation and the lower part of the spadix is stylized.

8. Alocasia amabilis W. Bull was validly published in the above-cited retail list, and is neotypified with material preserved by Brown at Kew from a plant obtained from Bull under that name.

CULTIVARS: As detailed in the Notes section above, the Longiloba group is most varied, and only a few named cultivars are regnized: Alocasia longiloba ‘Denudata’, Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’, Alocasia longiloba ‘Silver’, Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’

HYBRIDS: Alocasia longiloba is the most prolific parent in Alocasia hybrids, having been used in hybridization efforts since the mid 1800s. Beacause of this please note that some of these hybrids have been recorded historically, but may not longer exist in collections, if at all:

Alocasia ‘Amazonica’ (Alocasia sanderiana x Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’)

Alocasia ‘Argyrea’ (Alocasia longiloba x Alocasia ‘Pucciana’)

Alocasia ‘Bachii’ (Alocasia reginae x Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’)

Alocasia ‘Balloon Heart’ (Alocasia ‘Aurora’ x Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’)

Alocasia ‘Bambino Arrow’ (Alocasia longiloba x ?)

Alocasia ‘Chelsonii’ (Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’ x Alocasia cuprea)

Alocasia ‘Gaulainii’ (Alocasia odora x Alocasia ‘Pucciana’ - in literature as Alocasia ‘Putzeysii’)

Alocasia 'Ivory Coast' (Alocasia ‘Aurora’ x Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’)

Alocasia ‘Jean Merkel’ (Alocasia longiloba’ x Alocasia sanderiana)

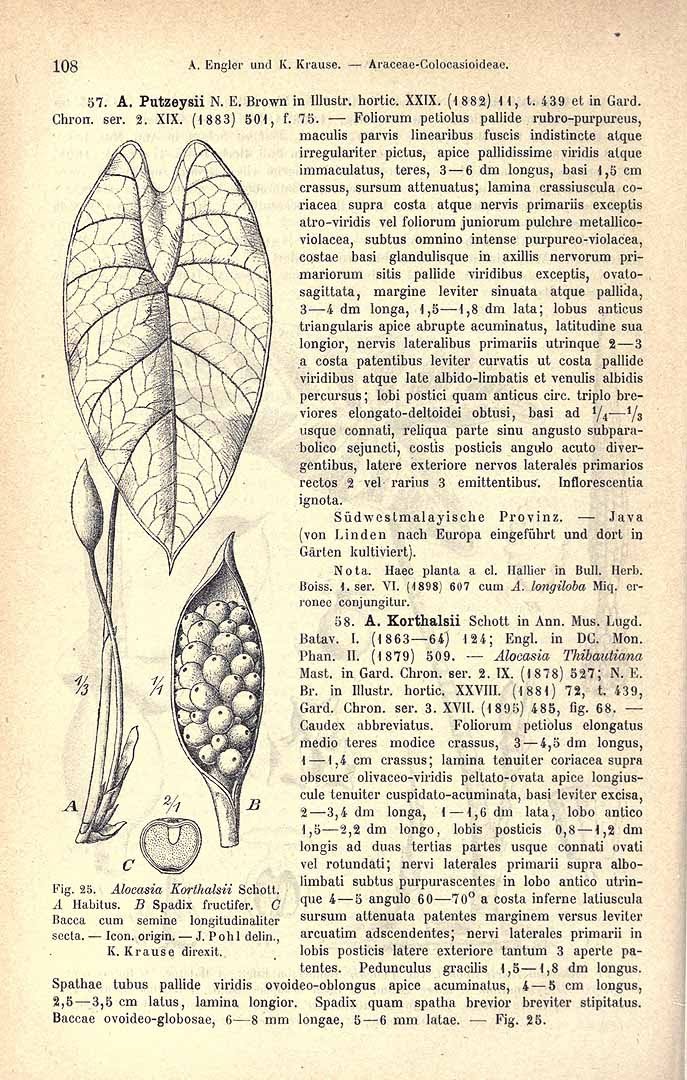

Alocasia ‘Kerchoveana’ (Alocasia longiloba ‘Putzeysii’ x Alocasia longiloba ‘Korthalsii’)

Alocasia ‘Kuching Mask’ (Alocasia longiloba x Alocasia macrorrhizos ‘Borneo Giant’)

Alocasia ‘Kutawatu’ (Alocasia longiloba ‘Grandis’ x Alocasia indica)

Alocasia ‘Loco’ (Alocasia sanderiana x Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’)

Alocasia ‘Louisville’ (Alocasia ‘Corazon’ x Alocasia longiloba)

Alocasia ‘Luciani’ (Alocasia longiloba ‘Korthalsii’ x Alocasia longiloba ‘Putzeysii’)

Alocasia ‘Mandalay’ (Alocasia sanderiana x Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’)

Alocasia 'Martin Cahuzac' (Alocasia longiloba ‘Korthalsii’ x Alocasia longiloba ‘Pucciana’ - listed as Alocasia longiloba ‘Thibautiana’ x Alocasia longiloba ‘Pucciana’)

Alocasia ‘Mark Campbell’ (Alocasia longiloba ‘Grandis’ x Alocasia sanderiana)

Alocasia ‘Moresby’ (Alocasia micholitziana x Alocasia longiloba)

Alocasia 'Mortefontanensis' (Alocasia sanderiana x Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’ (ovule))

Alocasia ‘Orchid Jungle’ (Alocasia cuprea x Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’)

Alocasia ‘Polly’ (Alocasia sanderiana x Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’)

Alocasia ‘Pucciana’ (Alocasia longiloba ‘Putzeysii’ x Alocasia longiloba ‘Korthalsii’)

Alocasia ‘Purpley’ (Alocasia sanderiana x Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’)

Alocasia ‘Rodigasiana’ (Alocasia reginae x Alocasia longiloba ‘Korthalsii’)

Alocasia ‘Sedenii’ (Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’ x Alocasia cuprea - listed as Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’ x Alocasia metallica)

Alocasia ‘Silver Arrow’ (Alocasia longiloba cross)

Alocasia 'Subodora' (Alocasia odora x Alocasia ‘Argyrea')

Alocasia ‘Venom’ (Alocasia sanderiana x Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’)

Alocasia ‘Wanda’ (Alocasia ‘Corazon’ x Alocasia longiloba)

Alocasia 'Watson's Giant' (Alocasia odora x Alocasia longiloba ‘Watsoniana’)

Alocasia ‘Zulu Mask’ (Alocasia odora x Alocasia longiloba)

REFERENCES:

Alocasia longiloba ‘Lowii’: Curtis' Botanical Magazine v.89 ser.3 v.19 (1863) Tab 5376

Alocasia longiloba ‘Putzeysi’: L'Illustration Horticole v.29 (1882) P.11

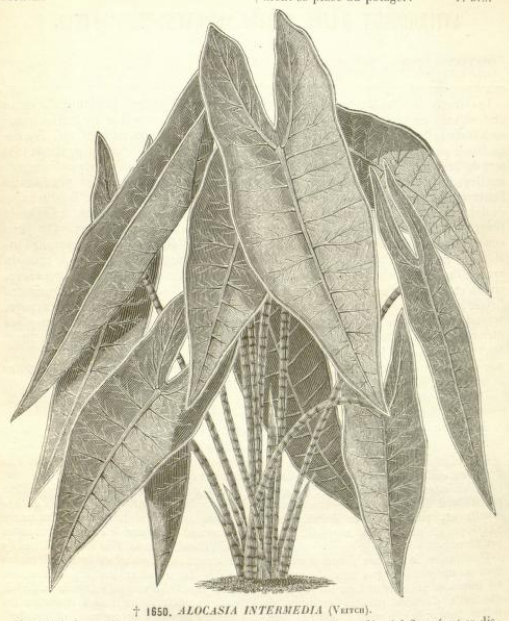

Alocasia longiloba ‘Intermedia’: Flore des serres et des jardins de l’Europe v.17 (1867-68) P. 168